We pitch this idea of operational user research as a means to scale and democratize user experience design practice across an organization. For decision makers already familiar with our user-centric-business gospel — reminder: aggregation theory demonstrates how the user experience is the differentiator for services that have no cost of distribution (because the internet is free); or: good UX is good business — but are concerned about costs, then all they need to hear is how a few tweaks to the workflow and a Google spreadsheet can get the wheels turning with little to no overhead.

It’s easyish to imagine how making the tools to curate feedback you’re already intercepting (emails, reviews, comments on Facebook) easy to use will over time aggregate a robust catalog of that feedback, which decision makers can use to gut-check their ideas.

That hot return on a small investment is why no-frills ResearchOps is hard to argue against. We often stop our evangelizing there.

The long game is interesting, though. Spin something like this up then take a gander at your organization’s RPG skill tree, where a few experience points and a snowball-effect leads you to the service reactor.

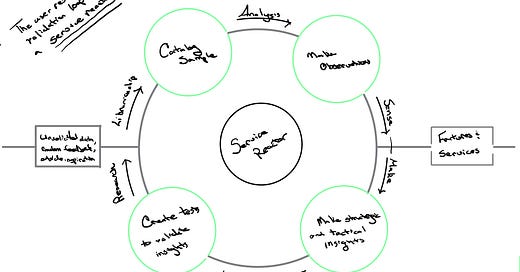

The service reactor is this work-in-progress model to demonstrate how a virtuous user research cycle and a commitment to discovery-validated delivery will generate enough proven insights to power a small city.

That’s a lot of made-up vocabulary designed to just consolidate this shit to a single sentence, so let’s break this down.

A “virtuous user research cycle” describes a system where your effort to make sense of some data results in the design of the next test to perform, the results of which return to the system.

“Discovery-validated delivery” is a requirement that end-user facing features of a product or service won’t be pursued until their demonstrable need and solution can be proven by existing user research.

A chain reaction beginning by cataloging raw data — survey answers, interview transcripts, a/b results, and so on — creates tactical and strategic insights, some aspects of which require more validation thus foreshadowing the next round of tests. Like a nuclear reactor, discovery-validated delivery creates pressure to perform those tests, which continues the chain reaction.

The chief product of the service reactor are insights that we use to validate our business decisions. At small scales, examples of these insights are:

evidence we need to rethink our menu structure because it’s confusing users,

indication that users need a way to opt-in to plain-text emails,

validation that this call-to-action works better than that one.

But as the catalog grows over time, new patterns emerge among unrelated sets of data, and that compounding value directly correlates to the scale of new insights. These are demonstrable proof that there is need among the userbase for entirely new services, let alone features. What’s more, because the service reactor creates insights as the byproduct of a process rather than insights that are specifically sought-out, the resulting service ideas may be orthogonal to your existing service provisions.

This is the drill maker getting into the business of designing entertainment units*. A service reactor powers the “innovation mill.”

The most important ethic I’m trying to convey with the service reactor is that while it is a vision to motivate an organization’s investment in ResearchOps, it is fundamentally user centric. Over time, there is no part of a service or product that is not derived from user research. The reactor ionizes the air with user centricity. You can’t help but breathe.

Note: The drill metaphor is one of the core fables to the jobs-to-be-done approach to design thinking. It basically explains how the drill-maker that is most successful when their drill is an aisle filled with other drills is the one who realizes that people aren’t buying a drill but the mounted television on the wall. The drill is a means to the end. What I’m saying is that an orthogonal business for the drill-maker is in entertainment units: both drill and furniture are means to an end when the job-to-be-done is to relax in a finished living room.

Liking (❤) this issue of Metric is a super way to brighten my day. It helps signal to the great algorithms in the sky that this writeup is worth a few minutes of your day.

Metric is a podcast, too, which includes audio versions of these writeups and other chats. You’ll find it in your favorite podcatcher.

Remember that the user experience is a metric.

Michael Schofield

Share this post